A Field Guide to Hallmarking

Every year we welcome thousands of visitors to Goldsmiths’ Fair, where they have the chance to see, try and buy some of the most exciting pieces of independent contemporary silver and fine jewellery being made in the UK today. The integrity of our exhibitors is beyond reproach, but with precious metal prices at an all time high, you could be forgiven for wanting to know the exact composition of the pieces that you’re looking at. So as a consumer, how can you tell that the golden ring you’ve slipped onto your pinkie is really 18ct gold, and that the candlesticks that would look amazing on your mantlepiece are truly Britannia silver?

Despite Hollywood’s historic portrayal of pirates, cowboys and highwaymen biting into golden coins to verify their metal content, it’s not possible to know what type of precious metal an object is made from by touch, taste or sight. To truly know that a gold-coloured ring is made of gold and what the fineness of that gold is, the metal needs to be scientifically tested in a laboratory by an Assay Office. Until relatively recently this was most commonly done by scraping off a small sample of the metal to be tested in the laboratory, but today, thanks to a process called X-ray Fluorescence Spectroscopy (XRF), most items can be tested without the need to take a physical sample of the metal.

Results in hand, you can now prove to the world that your gold-coloured ring, that has been independently tested (or assayed), is made of gold, and that the gold is 9,14,18,22 or 24ct. To tie the results of the test to the piece that was tested, the item is permanently marked with a laser or punch as a ‘hallmark’. Hallmarking is one of the oldest continuous forms of consumer protection – tracing its origins to medieval England and the reign of Henry II – and takes its name from Goldsmiths’ Hall, the site of the UK’s first Assay Office which opened for business in 1478.

Today, hallmarking is regulated by the British Hallmarking Council (BHC), and under the Hallmarking Act (1973) it is a legal requirement for all precious metal items over certain weights (7.78g for silver, 1g for gold, 1g for palladium, 0.5g for platinum) to be assayed and hallmarked before they can be sold.

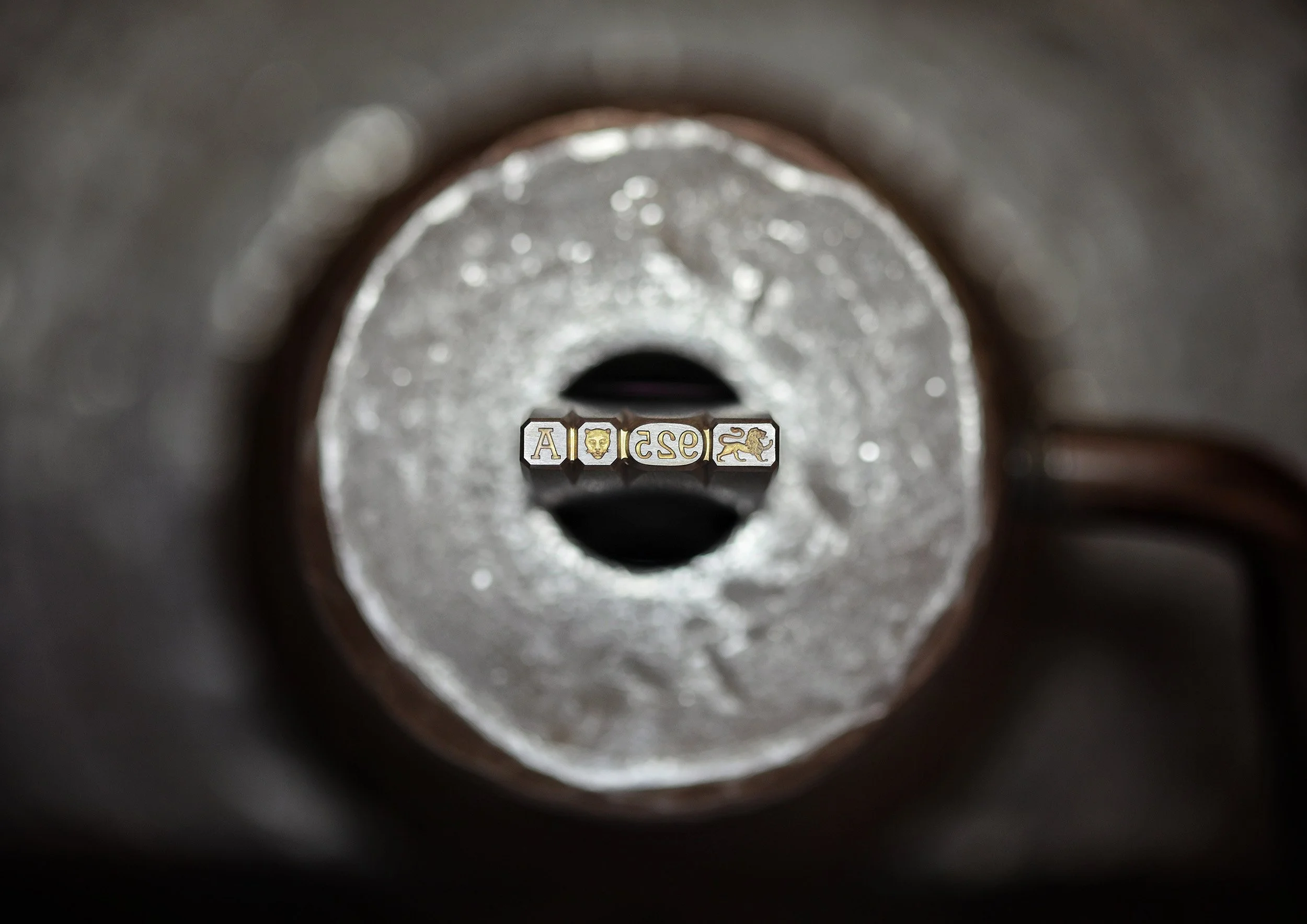

The full UK hallmark is made up of five component parts, three of them are compulsory and two are optional.

Sponsor’s Mark

The Sponsor’s Mark (sometimes known as the Maker’s Mark) is compulsory and tells you who sent an item in to be assayed. Normally this is the person or company who made it, and the mark is composed of their initials inside a shield shape. The Sponsor’s Mark must be a minimum of two letters and a maximum of five letters. Each one is unique. To ensure that makers with the same initials don’t get mixed up, two different fonts and 45 different shield shapes are available to choose from.

Traditional Fineness Mark

The Traditional Fineness Mark is optional and tells you whether an item is made from Sterling silver, Britannia silver, gold, palladium, or platinum. It was superseded in 1999 by the Millesimal Fineness Mark which provides more information.

Millesimal Fineness Mark

The Millesimal Fineness Mark is compulsory and tells you which precious metal an item is made from and how pure it is on a rating from 0–1000. A 999 mark means that the precious metal is as pure as it can be. The purity mark for each precious metal has a different shaped border, making it easy to tell the difference between metals that share the same colour, like silver and platinum.

Assay Office Mark

The Assay Office Mark is compulsory and tells you which of the four independent UK Assay Offices tested and hallmarked an item. Each Assay Office has a different mark – a leopard for London, an anchor for Birmingham, a rose for Sheffield, and a castle for Edinburgh.

Date Letter

The Date Letter is optional and tells you in what year an item was hallmarked. It changes annually on January 1 – with a new typographic alphabet being issued every 25 years. The font, case, and shield shape around the letter change once the alphabet has been completed so each letter is unique to a specific year. On 1 January 2025, all four UK Assay Offices began using a new uppercase typographic alphabet for their date letters, with the first letter being an uppercase 'A'.

Primed with this information you’re now ready to explore the world of precious metals, safe in the knowledge that when you Look for the Leopard, Ask for the Anchor, Request the Rose, or Check for the Castle you're benefiting from seven centuries of consumer protection. Happy hallmark hunting!

Written by Chris Mann | Photography by Paul Read and Chris Mann