Megan Brown - Woven with silver and gold

“The most important thing for me, is to recreate the life of woven textiles in the metal. It’s about the feeling of fabric in my work, not just stiff metal weaving, but really replicating the sensation of silk.” – For Goldsmiths’ Stories, writer Kate Matthams talks to Megan Brown about alchemy and transformation, the importance of supporting heritage crafts, and the magical process of weaving cloth from silver, platinum and gold.

Megan Brown’s creative practice is one of alchemy and transformation. Originally from North Yorkshire, the London-based jeweller and artist weaves together strands of gold, silver and platinum wire, creating something altogether softer that sits between metal and textile. “Metal has a lovely quality whereby you can push it to its limits and then bring it back again — I love that it’s such a cold and solid material, yet I can make it into a fluid fabric,” she tells me. “Being able to change the materiality of it, is really exciting.”

Conjuring a new object from raw materials is the very definition of handcraft, and it’s a concept that runs through Brown’s blood. Her family run Alfred Brown Ltd, a textile mill near Leeds which was founded by her great-great-grandfather Herbert Brown in 1915. It has been producing fabrics almost continually ever since, and is one of the UK’s remaining mills, a thriving business which produces fine worsted for tailoring. Growing up, “my ancestors were pawnbrokers, jewellers and weavers and we still have jewellers in the family,” she says. “The mill was very much part of family life. We would go after school and Dad would bring home fabric samples; it was a familiar place with familiar people. The machinery stood out the most for me, I found it fascinating.” This early interest in technique, the ‘how’ of the making process, would eventually fuel her exploration of wire weaving, to create jewellery and objects that are rich with heritage.

Brown initially studied fashion at Edinburgh College of Art. She loved the course, but found she was spending too long on each garment and becoming too absorbed in the details to produce what she needed within the timeframes available. She realised fashion wasn’t the right medium for her creative practice, and a timely year out due to ill health gave her a chance to reflect and try out different disciplines. One of them was jewellery, which appealed to her for its history, and intimacy as a channel through which we can capture moments in time; passing on jewels imbued with meaning. She had presumed she would establish a career in fashion, but “when I left Edinburgh and began to think about it, I realised that underneath it all, was the mill. It had been inspiring different things in my creative practice and I began experimenting with weaving to make much smaller and more detailed pieces.” She began working alongside a goldsmith in Harrogate doing repairs and remodelling, and ended up spending three years learning on the job. “it was like an apprenticeship to learn the craft,” she tells me. “I’m traditionally taught and if you know how to repair jewellery, then you know how to make it. It gave me a firm foundation and the knowledge to explore my own contemporary ideas and create more complex pieces.”

She began by exploring chain weaving in early pieces like the Gold Blanket earrings, which combine fluid woven gold chain with shoulder-tickling fringes, inspired by the archive ‘blankets’ at her family’s mill. These historic pieces of fabric are weaving samples of different patterns which come together to create a tapestry effect, which she describes as “snapshots of the moments in time when new designs were being created.”. Although it took time for her artistic direction to fully evolve, today, her creative language is a clearly defined melding of her family weaving heritage, and a love of precious metals.

“Covid lockdown was also good timing for me,” as it allowed her to focus on designing and developing different techniques, working out what inspired her, and moving towards a gradual homecoming to weaving. She launched her first collection through The Goldsmiths’ Centre’s showcase for emerging talent, Shine, which was digital-only in 2020, and went on to study silversmithing at Bishopsland Educational Trust, where she mastered techniques like chasing (reverse hammering to create a raised design in metal); raising (hammering over a curved surface to create a bowl or vessel shape); and engraving. As she became more familiar with the material, Brown became interested in creating more sculptural work, that was “full of light and movement” and was awarded a grant by the Worshipful Company of Weavers to create a sculpture, “which was wonderful — sometimes you have ideas that never come to fruition, but this allowed me to work on a larger scale.” The result was The Veiled Sculpture; an undulating silver vessel raised with the help of silversmith Oscar Saurin, which acts as a plinth to display her biggest piece of woven metal yet, a fine mesh created with strands of silver fused with 24ct gold. “I was inspired by Classical veiled marble sculptures,” she says, “I love the way the marble can look like a translucent fabric and I wanted to see my weaving draped like that, as well. It was handmade and time-consuming, and I love that.” The vessel was the centrepiece for the 400th anniversary exhibition of the Worshipful Company of Gold and Silver Wyre Drawers, and has inspired her to make a wall hanging in the future.

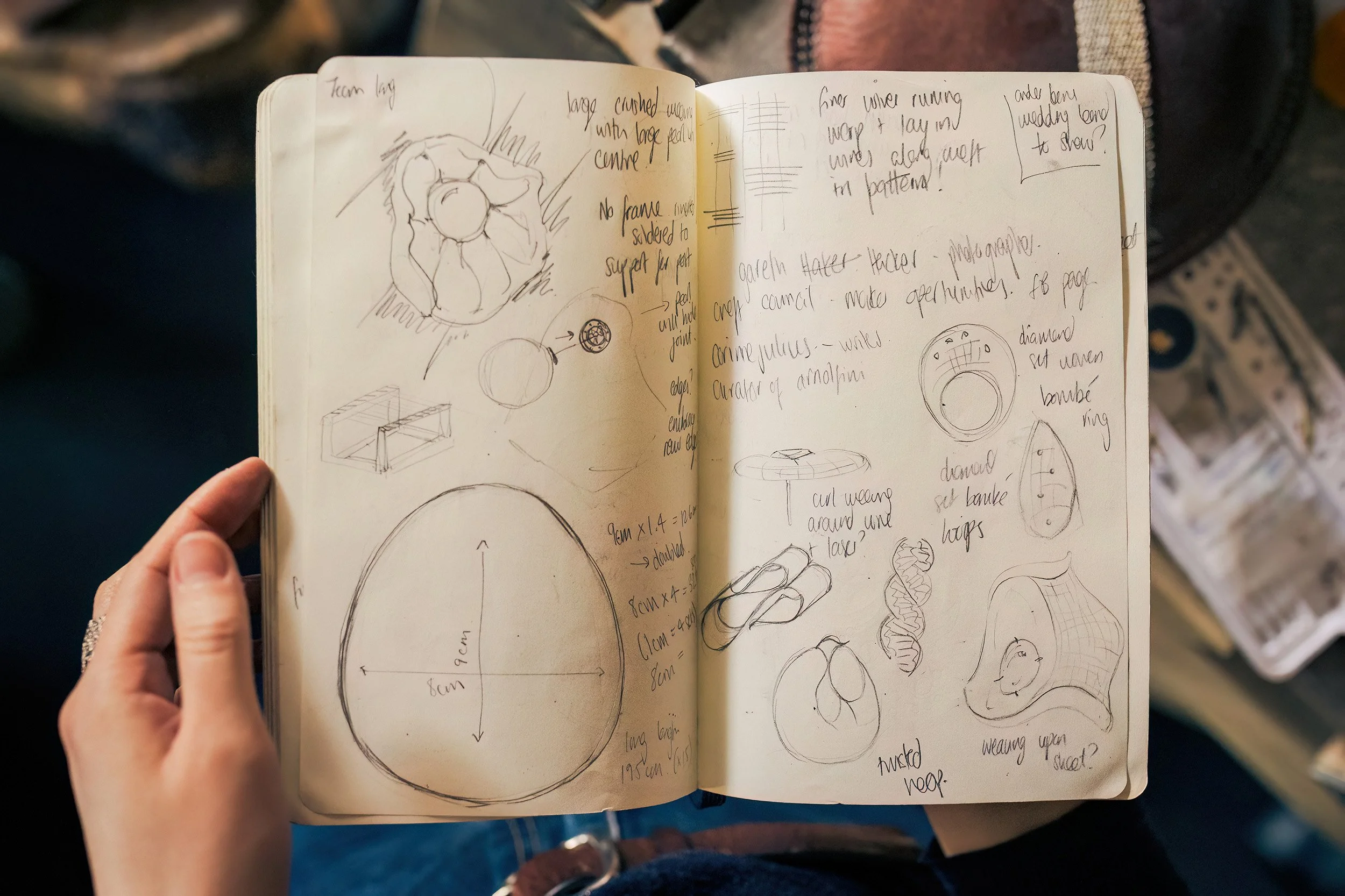

From vessels, back to jewellery. As her practice began to gain traction, she experimented with different materials, moving further into her craft as a metal weaver. From very light and delicate pieces, like the chain-woven hoops that curl gently behind the ear that became emblematic of her style, she was drawn to focus on form and looked to wire. “Learning silversmithing techniques gave me the skills to move and form the wire and try out different materials,” she explains. Gold and platinum, while expensive, have qualities that make them perfect to weave with, while titanium might be great for adding colour, but presented technical problems as it can’t be soldered. “Sometimes, when you start using a material, the piece can take a different turn into something else. I love that unpredictability, it’s what makes each design unique and allows me to really push the concept to its limits.”

Today, her work marries simplicity of form with the complex texture of hand-woven metal, and Brown now weaves using the ancient Persian technique of Hasir Bafi. Traditionally used to make reed matting, she found the method enabled her to weave with gold and silver wire on a much tinier scale, creating a precious fabric that could be draped and moulded at will. “The most important thing for me, is to recreate the life of woven textiles in the metal. It’s about the feeling of fabric in my work, not just stiff metal weaving, but really replicating the sensation of silk. I can sculpt with the wire weavings I make, it holds its form really well.” She increases or reduces threads to create different forms, then cuts the woven material and fuses the ends together before shaping it. “I’m currently refining the edging,” she says, “It’s important to consider it in the design.” In one ring, the band is left open, with a stone set at either end to finish the piece, while in the Golden Silk bracelet, a two-tone gold and silver piece of weaving that slips like liquid over the skin, chain is woven directly onto a silver clasp.

In the magnificent Woven Bombé ring, the ends are tucked into a solid open structure, the weaving stretched taught so each tiny metal thread can be seen, holding the form in place. Its charm lies in the irregularities of the handcraft, the way she allows the strands of metal to go their own way, before bringing them back into line. “I’m really inspired by the sculptural form and through weaving I can bring texture. I develop them both simultaneously, to create a stronger material that also informs the way it feels to the touch.” Brown looks to artists like Catherine Martin, the first Westerner to graduate in Kumihimo, the Japanese art of braiding, with which she creates minutely textured jewels that marry force and delicacy, refining a single technique to produce “work which is very much her own, that I love.”

Most recently, Brown has begun experimenting with adding colour to her jewels. She had previously used yellow and white toned metals, or fused gold onto silver wire weaving (in the award-winning Woven Box), and is now introducing colour through stones. “I met Tom Scott, who worked with Andrew Grima, and has been making jewellery for over 50 years. Through his understanding of wire and stones he has been able to advise me on how to move forwards.” Working with gemstones requires more complex shapes and forms and these restrictions have required problem-solving that has made the design process more enjoyable. Swirls of pink and purple in a vibrant opal set in gold, contrast with oxidised silver on a choker, while elsewhere, a bright silver bombé ring is scattered with deep red, gold-set garnets and a yellow sapphire winks out from woven platinum and white gold, its geometric emerald cut accentuating the cross-hatched wires.

In 2023, Megan came to the end of a year-long residency at the Sarabande Foundation – set up by fashion designer Lee Alexander McQueen CBE in 2006 to ‘support the most fearlessly creative minds of the future’ – where she was able to work alongside artists and craftspeople from different disciplines, fuelling her creativity through the exploration of concepts and experiences from industries outside of her own.

The peer-to-peer transfer of skills and knowledge and the cross pollination that occurs whenever creative people meet, sits at the heart of the human story, and as an artist who has learnt her craft through the training and mentorship of those who came before her, Brown is a fervent believer in the need to champion, support and nurture the skills required for the heritage crafts to flourish.

“It’s a worrying time for heritage skills with many that are vital to the jewellery industry at risk as people retire and their skills and knowledge go with them. I think it is vitally important that we do everything we can to use, retain and pass on practices that are so deeply woven in to the fabric of who we are, the objects we possess and the stories that we tell. Through the mill I got a level of exposure to heritage craft that has helped to shape my practice and hammered home the importance of understanding how things are made. I’m incredibly proud to carry on that story through the pieces that I make and the precious materials that I use.”

Written by for Kate Matthams for Goldsmiths’ Stories | Photography by Paul Read