Jewellers and the City: finding inspiration in the urban environment

Inspiration for jewellery can come from many sources, both concrete and conceptual – for Goldsmiths’ Stories, writer Rachel Church explores the impact, effect, and inspiration of cityscapes and the urban landscape on the practice of contemporary craftspeople Daphne Krinos, Jonathan Boyd and Vicki Ambrey-Smith.

Inspiration for jewellery can come from many sources, both concrete and conceptual – the natural world, wider artistic movements, the narrative of the jeweller’s life, a response to a social or intellectual movement but for a select group of jewellers, this inspiration comes from the city and the urban landscape.

The jewellers of the early twentieth century were probably the first to model their jewellery on the life of the city and the modernity of cars, trains and industrialisation. In 1930 the modernist jeweller Raymond Templier claimed that “As I walk in the streets I see ideas for jewellery everywhere, the wheels, the cars, the machinery of today. I hold myself permeable to everything”. Three contemporary jewellers – Vicki Ambery Smith, Jonathan Boyd and Daphne Krinos have found inspiration in the city, in the shapes and details of city buildings and streets but also in the emotional and biographical context of the places in which many of us live.

Vicki Ambery Smith’s jewels are all about the buildings of our great cities, edited but recognisable versions of familiar places. Her jewellery takes its imagery from buildings which often have a personal meaning to the wearer and transmutes them into brooches, earrings, cuff-links and necklaces.

Architecture was a very early source of ideas – “I fell into it when I was still at college…and I would never have thought that I would still be doing this theme now, forty years later, but it’s much more specific architecture now”. She grew up in Oxford, surrounded by the buildings of the university, although says that she didn’t think of it as anywhere exceptional or special until she left it.

Her desire to become a jeweller was formed on her art foundation course, having first considered architecture and theatre design. She realised that “small scale 3D was my thing and architecture and theatre design were just too big – I don’t need planning permission for my buildings!” She trained as a jeweller at the Hornsey College of Art which honed her craft and design skills on the jewellery course which had been established by the German jeweller Gerda Flöckinger.

“You have to make a decision, whether to be completely uncompromising about what you want to make and whether you can make a living through that”, she explains. “I’ve been lucky enough to be able to do this as my only job for forty years.”

Her work these days is almost exclusively commissioned, often through Goldsmiths’ Fair, where she meets people who ask her to make an object based on a building or city which holds a particular meaning for them. Her work has been based on domestic architecture and private homes as well as great public buildings, creating objects which invoke the spirit of the building rather than offering a miniaturised copy. She uses photographs supplied by the customer as well as online information and creates beautifully detailed paper maquettes to finetune details of perspective and proportion. The finished piece is an edited version of the original, a portrait of the building rather than a reproduction.

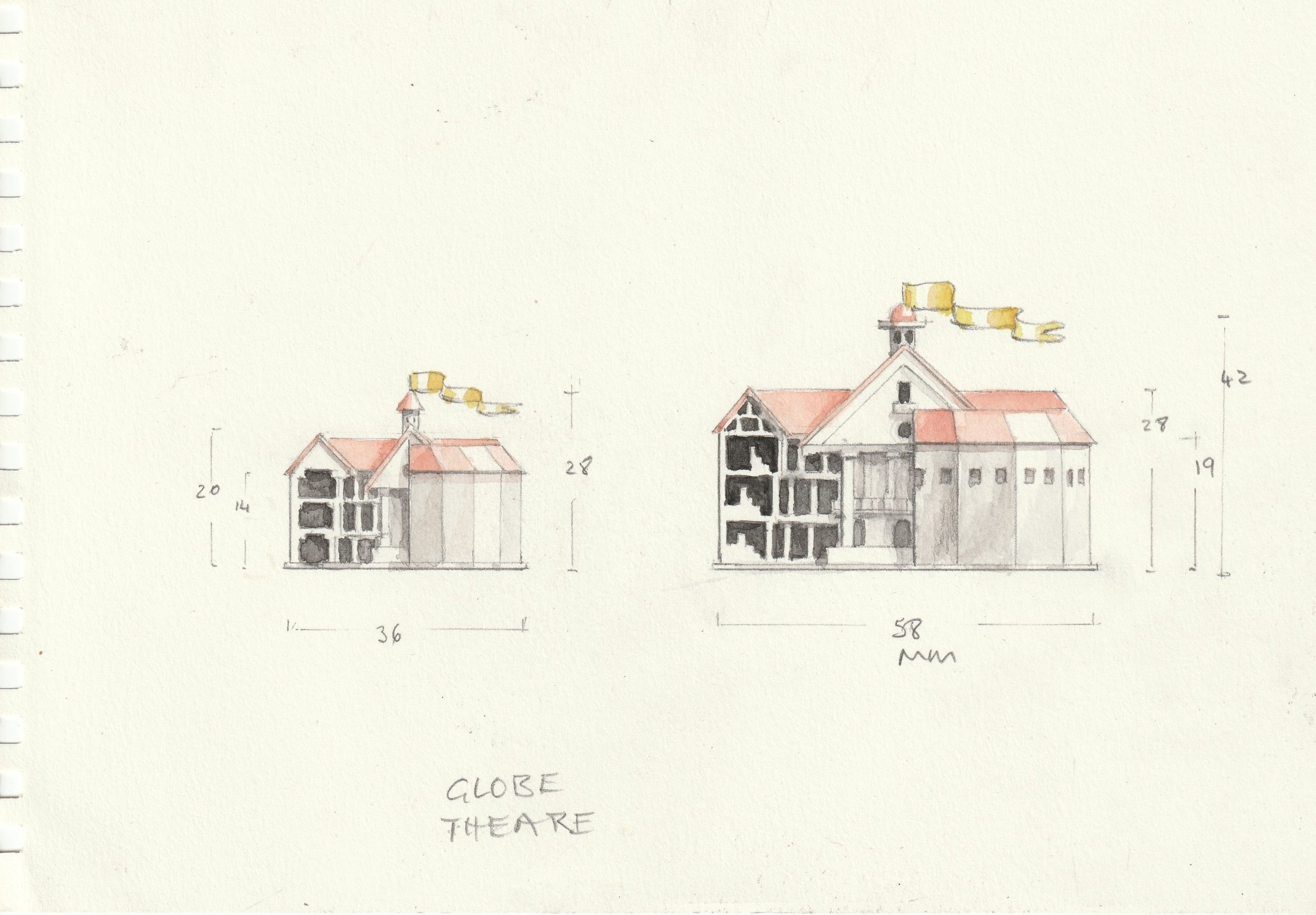

Her early work sometimes included a floor plan or architectural design as part of the piece and more recently, she has included the interiors of buildings. As she explained, “there’s something honest about showing the inside of the building – a lot of buildings can be about grandeur and pomp, flashing the cash. Including the interior is a way to show what the building is there for.” A set of brooches of Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre include the interior as “the theatre is all about the stage … so a cross section of half the inside, half the outside explains the whole building.”

Looking at her work offers a tour of the world on a tiny scale – the palaces of Venice, the architecture of Amsterdam, Reykjavik, Croatia, Oxford and Cambridge, the opera house in Sydney and the cityscape of Birmingham. Many of the major sights of her hometown of London are recorded in silver – St Paul’s Cathedral, Mansion House and the Royal Opera House as well as modern buildings like the Shard. Classical and Baroque architecture works well, but she feels that some buildings cannot be satisfactorily scaled down, fearing that attempts to recreate London’s ‘Gherkin’ (30 St Mary’s Axe) would end up looking like a bullet.

The calm shapes of her buildings are closely tied to important moments in the lives of her clients – commissions to mark weddings, anniversaries, important birthdays and graduations, or made to commemorate leaving a beloved house or memories of university years, demonstrating how buildings can stand in for a family relationship or moment in time. A ring based on the Olomouc synagogue brings this biographical aspect vividly to life. The synagogue in the Czech republic was completely destroyed by a fire set by Nazis in 1939. The commissioner’s father had worshipped at the synagogue and she wanted a ring, based on the form of a traditional Jewish wedding ring, as a memorial to her father and to the lost building. A gold and platinum mesh brooch of the Snowdon Aviary at London Zoo was made for the daughter of its engineer, Frank Newby, the client herself a dealer in twentieth century jewellery. Although the brooch is entirely flat, the clever use of perspective makes it appear three dimensional and instantly recognisable.

“Every morning on my way to work I walk past the sunrise over Lidl and it is beautiful” is the evocative title of one Jonathan Boyd’s brooches. While Vicki Ambery Smith takes her inspiration from the buildings of cities both known to her and unknown, Jonathan Boyd uses images of the city he lives in and the typography he sees around him to explore urban architecture and language. He describes this process as “non-linear, non-narrative and non-conformist”.

Boyd’s city is the landscape of supermarkets, industrial estates, street furniture and the ubiquitous text of brands, adverts and signage. In a research project he recorded and counted the words you see as you walk through the city and made it out to be 40,000 words every ten minutes, a saturation of language and typography. Words and the city are two of the most important aspects of his work which he united in an alphabet created from the typeface of major brands, the D of Disney and unmistakable M of McDonalds which dig themselves into the consciousness of the city dweller.

He speaks of being super excited by the “frenetic complexity of the city – that sort of energy we can get from a city”. His city landscapes often have a personal or “auto ethnographic” quality – the budget supermarket he walks past, the street in which his daughter was born, the sights of his daily walks. He was born in Aberdeen and studied at the Glasgow School of Art and then the Royal College of Art in London, where he is the current Reader in Jewellery, and describes himself as “the product of the city – the urban environment is central to my thinking. It’s essential to my practice”.

His sense of place is very much rooted in his own experiences – one of his neckpieces, “The M8 Intersection at Charing Cross as a Metaphor for my Heartbeat” can be seen as a love letter to the city – a modern city which could put a motorway right through the centre but is also a historic jumble of Victorian and Edwardian tenements. The visual aspect of the city is not the only element referred to, the motorway also provides “the soundtrack of your life, this constant low humming” like the heartbeat of the city itself. Boyd’s work is as much a reflection of the experience of living in a place as a representation of the place itself.

His eye finds the poetry in the “underseen and overlooked” elements of the urban world – a group of brooches now in the Goldsmiths Company collection create a rose, lily and dandelion through the assembly of multiple photographs of street furniture and urban detritus. The rose is made from disused carpets, the lily from traffic cones and road signs, the dandelion from steel pillars, transforming these gritty and unromantic objects into flowers, the mainstay of so much jewellery.

The softly coloured gold and bright gemstones of Daphne Krinos’ jewellery are reminiscent of the light and colours of her native Greece but, like Vicki Ambery Smith and Jonathan Boyd, the city has also been a powerful force of inspiration. She grew up in Athens and moved to London to study art and subsequently jewellery, at Hornsey College, in the same cohort as Ambery Smith. The students were encouraged to sketch the world around them and take inspiration from their surroundings. This became a way for her to find her feet on the course, as she says “The very first projects I had, they didn’t make sense to me. I was Greek, I didn’t speak good English, I was quite, sort of lost. I didn’t know how to deal with projects or what my tutors expected of me but quite quickly, I slipped into the habit of going out daily and just sitting somewhere, mostly near college and drawing what I could see in front of me.”

This close study of her environment, along with one of the first college projects which really made sense to her, led to a study of positive and negative spaces, which is something which has returned to her work more recently. “The more solid pieces I’ve been making in the past two or three years have definitely come, not necessarily from drawing positive and negative shapes of buildings but actually taking photographs of them and really honing in on these kinds of areas which I find interesting and they come into my work, and there you go – back to a project I did in 1975!”

Her early work often involved open structures and frameworks around gemstones because, as she explains “I used to be fascinated by fences around buildings and sometimes temporary fences and also building sites. I used to take loads and loads of photos around building sites and the structures of gasometers, so my work had a sort of open, structural look to it, certainly in the early noughties.”

Photography has taken the place of drawing in her practice and she walks around her neighbourhood of Hackney, in East London, part of the city which has changed at pace in the last twenty years, photographing buildings both ruined and complete, construction sites, graffiti and the small details of the urban landscape. She sometimes prints the pictures, to chop them up and create rough collages which may then become the basis for future jewels, part of a process of model making and three dimensional exploration which has taken the place of sketching.

Although urban landscapes were the inspiration behind much of Krinos’ jewellery, some pieces have an even more direct link. The necklace with which she won the 2017 Boodles and Goldsmiths Company Ambassador Diamond Necklace Competition is based on the view of Canary Wharf, London’s financial centre, from the hilltops of Greenwich, seeing the lit up office buildings glittering in the night sky. She was always struck by the way the lights shone all night but also found them “incredibly pretty – I’ve always thought of diamonds and always wanted to make something that evokes this image of the city at night”.

The competition brief to make “a large sculptural piece where the diamonds were the heroes” presented the perfect opportunity to realise this vision, making a necklace in which the abstracted silhouettes of office buildings were made of 18 carat white gold plated with jet black ruthenium and set with very white diamonds to represent the luminosity of the city at night. The building silhouettes are separated by tiny models of steel girders, making the necklace a portrait of both the finished buildings and their genesis in building sites.

Although their work is very different, each of these exceptional jewellers has looked at the city with their own eyes, finding the emotional and personal meaning behind the places we live and grappling with the problem of relating architecture to the human body to create their own individual, creative and effective solutions. Their jewels are conversation starters – taken from the life and experience of the city and its inhabitants and able to make a connection with those around us.

Written by Rachel Church | Photography by Paul Read, Richard Valencia, Daphne Krinos, Vicki Ambrey-Smith